If this fallacy was not enough, they had, furthermore, allowed explanation to be replaced with value judgement. Pushed by nationalism, they had all too easily conflated and confounded the understanding of the causes and the quest for the origins. Yes, Bloch conceded, historians had failed.

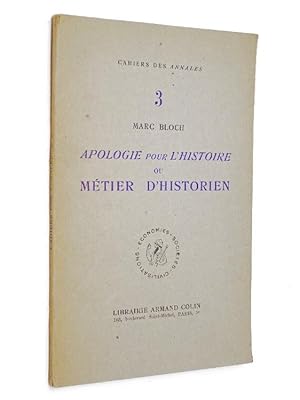

Yet he also felt that the very tools which enable us to understand the past were under attack – in part because historians themselves had been seduced by a ‘satanic enemy’: nationalist ideology, as he stopped short of defining it. And isn’t Bloch’s Apology for History or the Historian’s Craft ( Apologie pour l’histoire ou le métier d’historien) named after the Apology of Socrates? Why would Bloch write a treatise on The Historian’s Craft, as the shortened title of the English translation unfortunately suggests, when, indeed, he felt the need to write in history’s defence? As Europe went through one of its darkest hours, Bloch sought to understand what unfolded under his trained eyes – and how magnificently he did it in The Strange Defeat. For both Bloch and Kantorowicz remind us of what Bloch called the ‘demon of origins’ in his very last book.īloch’s ‘demon’ is an obvious reference to the spirit that used to speak to Socrates in form of a capricious voice, and which the philosopher consulted before taking an important step. While I might ponder this at more length in another context, I would like to recall some reflexions of two of the most important historians of the 20 th century by any standard, two fellow medievalists as it happens, namely Marc Bloch and Ernst Kantorowicz.

The piece in question is not terribly original, yet it is precisely in its triviality that its danger may reside. I have been asked to reflect on the piece by the group ‘Historians for Britain’ in History Today.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)